rowing up, I never realized how tattoos negatively influenced the way my family was looked at by cops and courtrooms.

Part of my upbringing was spent in Venice with family members always in and out of jail. Tattoos were the norm. Cursive names, bare-breasted payasas, spiderwebs, suns, moons, even makeup. Every aunt, uncle, cousin, sibling, and parent had something. Eventually, I had them, too. A pair of sparrows on my back when I was 17. Later, a portrait of Lucille Ball on my left arm. Now, too many to keep track of. But always black and gray.

“[Back in the day] it didn’t matter if your tattoo was believed to be gang-related or if it was just a flower, you were looked at and treated differently. Police also associated tattoos with intravenous drug use,” my mom recalls. “If you had a tattoo on your forearm, you would immediately be asked if you shot-up, and you were subject to search and scrutiny.”

Habitually and historically, tattoos have been linked to gang membership and crime in L.A., and that linkage exacerbates law enforcement’s compulsion to profile. Thus, having tattoos has silently and systematically become synonymous with ill intent, and despite the increasing normality of ink, being a tattooed Angeleno (especially one of color) remains problematic when it comes to profiling and suspected crime-involvement.

Tattoos do not always equal gang involvement

In 1991, my uncle Gary and cousin-in-law Lynton were accused of stabbing a man outside of the Brig Bar in Venice. The man, Jose Andrade, claimed that my cousin “politely” led him outside to converse. There, my uncle was allegedly “standing by [a] light post holding a knife.” Andrade survived the incident, sustaining a laceration to his liver. It’s worth mentioning that prior to the trial, Andrade didn’t know my uncle or cousin. Instead, Andrade’s friend Don Duvall “put it all together” for him, naming Gary and Lynton as the assailants.

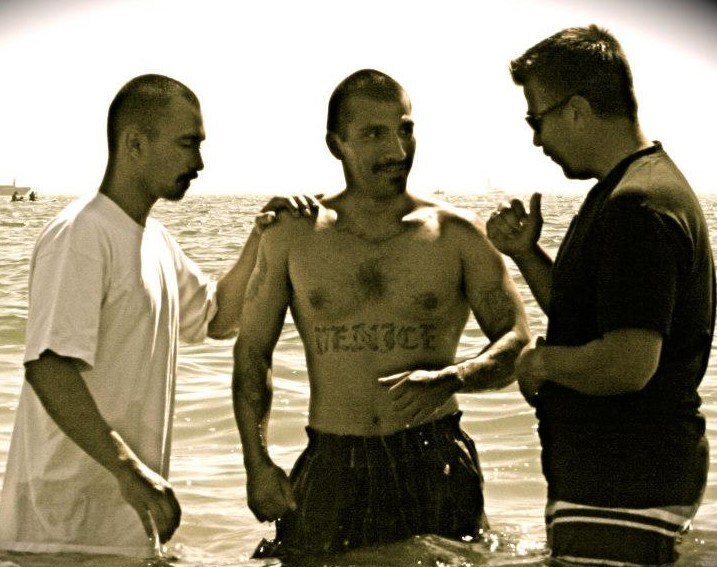

Part of the prosecution’s claim was that both my uncle and cousin were members of Venice 13—a prominent Mexican gang in L.A. Once their tattoos were examined, it was revealed that my cousin Lynton did, in fact, have a V13 tattoo. However, he asserted that he’d received the tattoo 12 years prior to the trial when he was only 13 years old. Similarly, my uncle explained that he had received his “Venice” tattoo “about 20 years ago…only because he lived in Venice.” There was no evidence presented by the prosecution disputing the age of either tattoo. More importantly, LAPD officer Steven Alva, the gang expert assigned to the case, attested that neither my cousin nor uncle appeared on the detailed gang-member list he’d spent 18 months creating.

Despite verifiable alibis, witness-accounts corroborating their innocence, and conflicting statements made by Andrade, both were found guilty of “assault with a deadly weapon causing great bodily injury.” My uncle was sentenced to 13 years in prison; my cousin, six.

Two years later, they appealed their conviction, asserting that the prosecution used their Venice-related tattoos to falsely influence the court. They maintained that despite the overpowering evidence of innocence, their tangential tattoos ultimately swayed the judgment. The case was won and the charges were overturned. The transcription from the appeal states that the erroneous connections made between the tattoos and gang membership ultimately “resulted in a miscarriage of justice.”

Tattoos, law enforcement, and a life taken at 26

A couple of decades after the Brig Bar trial, my cousin Eric was shot and killed by a Huntington Beach police officer named Jason Heilman. Eric had moved from Los Angeles to Orange County (where I lived with my mother, brother, and step-dad) seeking a fresh start, a way to break free from the deep entanglements of growing up in the ghettos of L.A. For years, he lived with us on and off. He was soft-spoken, well-mannered, and deeply loyal. He was also an aspiring tattoo artist.

The happenings of that morning in 2013 are still unclear to my family, but a letter released by the District Attorney’s Office offers this:

“[Officer Heilman] observed two Hispanic men walking away from a pickup truck…[He] noticed that the right taillight of the truck was broken and covered with tape…Officer Heilman decided to conduct a ‘consensual encounter’ with the subjects to find out ‘what they were up to’….Officer Heilman pulled up next to the subjects and spoke with [Eric]…Officer Heilman asked [Eric] if he was on parole or probation and he said ‘no.’ Suspecting that [Eric] was a gang member, Officer Heilman asked [Eric] what neighborhood he was from…Officer Heilman clarified by asking him if he was from a specific Hispanic criminal street gang in the City of Venice. [Eric] responded, ‘No, I’m just from L.A., from Venice.”

What allegedly took place next will haunt my family forever: Officer Heilman commanded my cousin and the other man to sit on the curb. He claimed Eric began fiddling with something in his jacket. Heilman reached for his gun. Eric ran. Then, Heilman alleges that my cousin stopped running, turned, took a “shooting stance,” and pointed what looked like a gun at him. A revolver with a broken trigger-spring was later recovered next to my cousin’s lifeless body; it had been fired three times. Heilman fired 23 rounds, shooting my cousin in the left shoulder, left forearm, left leg, left buttock, left hand, his chest, and his head. He was 26 years old.

The day of the tragedy, as we all stood behind caution tape staring at Eric’s body in the street, his younger brother recalled, “[the police] literally told [Eric] a week ago they were going to beat him up really badly or kill him…he got away from that bad lifestyle, but the police were still targeting him.”

I can’t help but feel it wasn’t the taillight that Officer Heilman first noticed, but rather a combination of Eric’s tattooed hands and arms and his Hispanic heritage. By definition, a “consensual encounter” is an encounter wherein the person(s) being approached feel free to leave or decline to speak. As soon as Heilman ordered my cousin to sit on the curb, he was technically in detainment, and detainment is only valid upon reasonable suspicion.

My cousin was not on probation or parole. He informed Heilman he was not a gang member. And he complied with all of his orders, even voluntarily offering Heilman the keys to his truck to be searched. My conclusion is this: Heilman was unreasonably suspicious of my cousin because he was both tattooed and of Hispanic descent. Period.

I reached out to the L.A. Public Defender’s Office regarding the problematic nature of tattoos in Los Angeles crime and possible solutions to the issue, but the attorneys declined to comment, stating that there was a lack of statistics and they “[couldn’t] conjecture as it could mislead.”

Just as my uncle Gary and cousin Lynton’s Venice tattoos were used to incarcerate them, I maintain that Eric’s tattoos played a powerful part in the profiling that lead to his death. Though Heilman’s profiling of my cousin by no means absolves Eric of any wrongdoing or the major mistakes he made that day, it does serve as an example of the cycle so many seem stuck in.

Tattoos are not always admissions of guilt

The use of superficial attributes as grounds to apprehend and convict is not only grossly opportunistic, it’s cyclical as well. Tattoos breed recidivism, and recidivism breeds tattoos. There’s no way out. My mom recalls her brothers and others from the neighborhood returning from prison more heavily tattooed each time and consequently under an exponentially larger microscope, not just because of their criminal records, but also because of their amassed ink.

None of this is to say that my family is made up of saints or martyrs. Criminal pasts and drug-use are attached to almost every member. It’s not to say that people with tattoos aren’t often guilty of crimes or associated with gangs either. And it’s not to say that tattoos are the primary or most frequent way people are profiled. This is to say, however, that there’s an unconstitutional fracture in the system, and tattoos play an indisputable part in that.

In his Rolling Stone article “Rap on Trial: Why Lyrics Should be Off Limits,” Erik Nielson questions why rap lyrics are continuously not considered art and instead considered an autobiography. Tattoos have historically been subject to similar scrutiny.

Though they are now protected under the First Amendment as a form of free speech, the most fascinating thing I’ve come to realize is that in the eyes of the law, tattoos are seen as admissions of guilt.

Such was the case in the trial of Anthony Garcia, the 25-year-old Pico Rivera gang member who tattooed across his chest a murder he’d committed. The tattoo was incredible rudimentary and, no doubt, done in his homie’s garage. Nonetheless, detectives considered the tattoo a “non-verbal confession” and he was sentenced to 65 years in prison. Though Garcia’s case is an extreme example and his actions are indefensible, his case serves as an absolute illumination that tattoos do, in fact, talk.

As it currently stands, families in L.A. even remotely resembling mine can’t walk down the street with inked arms and dark features without being moderately criminalized. You can’t tell me otherwise.

The normality of ink is steadily increasing; even some police officers have tattoos. In terms of profiling, the Department of Homeland Security analyst Ken H. believes there’s no way to completely disassociate all tattoos from crime because some tattoos are just intrinsically linked to criminal activity. And while I agree—I’d never suggest a swastika or insignia of hate go ignored. I still wonder if there’s a way to keep tattoos off-limits when it comes to profiling.

Nielson contends, “…[rap] is a kind of fiction—one that, like horror films or country songs, frequently relies on exaggerated depictions of violence…it is often intentionally hyperbolic as well, drawing on the long tradition of boasting and exaggeration.”

I contend that tattoos are no different, and his argument for lyrics offers up what I consider a possible solution for the Amendment-protected art form.

“We have to decide whether such speech is worth protecting.”

For Neilson, “the answer is obvious.”

For me and my dead cousin, it is crystal clear.

Appreciate this story? Support local journalism in Los Angeles and become a Member of L.A. TACO! You can join the Taco family and get super cool perks from our favorite taco spots, exclusive merch, giveaways and more. Join L.A. Taco Now.